|

| |||

|

The 1935 Alfa Romeo Bimotore: The First Ferrari? | ||

| by Thomas O'Keefe, U.S.A. | |||

|

In a sport whose history is full of technical experiments and breakthrough advancements, the 1935 Alfa Romeo Bimotore stands out as one of the most venerable projects - a race car with a unique and distinguished provenance, that traces its heritage back to two of motor racing's most evocative names: Alfa Romeo and Ferrari. A look back at the bright, brief life of this magnificent beast

Who can forget the Brabham BT46B fan car which raced once, won in Sweden and was promptly banned? The stillborn Ferrari V8 Turbo Formula Indy designed for Ferrari's assault on Indianapolis (which was an unrealized dream of 88 year-old Enzo Ferrari in 1986-87 that died with him)? The six-wheeled Tyrrell with four tiny wheels up front and which also won in Sweden (and the experimental six-wheeled Williams of 1983 with four wheels astern, which never raced)?

The elegant 1957 Vanwall VW6 streamliner; Vanwall's 1961 rear-engined VW14 dubbed the "Whale", raced once by John Surtees at Silverstone and the Vanwall Team's last gasp before closing its doors; the Connaught "toothpaste tube" streamliner; the 1940 Alfa Romeo Tipo 512 mid- engined flat 12 Prototype, which was built during World War II but never raced; the six-wheeled V16 Auto Union Type D Hillclimb car with four rear wheels; brief flirtations by Cosworth and Lotus with Four Wheel Drive in 1969-71; and the Mercedes-Benz 1.5 litre W165 cars developed specifically for one race, the Grand Prix of Tripoli in 1939, where the W165's promptly finished first and second and were then retired to Stuggart?

Even in the tightly restricted current era of Formula One, we have the crowd-pleasing two-seater McLaren-Mercedes and in Indy cars now, a two-seater Target/Ganassi/Reynard, which are currently a novelty but who knows: maybe in the future, we will revert to co-pilots sitting behind the driver doing data acquisition, race strategy or other on-board duties, a return to the riding mechanics of old.

One of the most venerable of these one-off projects is the 1935 Alfa Romeo Bimotore, a race car with a unique and distinguished provenance, that traces its heritage back to two of motor racing's most evocative names, Alfa Romeo and Ferrari.

The genesis for the Bimotore was the desperation of Alfa Romeo in 1935 in coming to terms with the growing German Menace - the formidable 3.9 litre Mercedes-Benz W25 B's of Rudolf Caracciola, Manfred von Brauchitsch and Luigi Fagioli with their characteristic shrieking superchargers and the ill-handling but powerful rear-engined 4.9 litre Auto Union Type B's of Hans Stuck, Achille Varzi and Bernd Rosemeyer. To be sure, Alfa Romeo had its own arrows in its quiver, including especially its driver line-up. At the personal insistence of Benito Mussolini, Tazio Nuvolari, the "Flying Mantuan", re-joined Alfa Romeo for 1935; Rene Dreyfus of France and Louis Chiron of Monaco, both legendary in their own rights, rounded out the Alfa Romeo factory team. But Alfa Romeo's Tipo B 3.1 litre workhorse, popularly known as the P3, was getting a bit long in the tooth by 1935 and while still competitive on certain road circuits, the P3's would be hopelessly outclassed by the German teams in the ultrafast Formula Libre (anything goes) events to be held at Tunis, Tripoli and in Berlin.

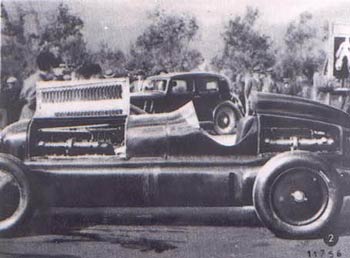

Enter the Bimotore, Alfa Romeo's answer to the German teams. As its name in Italian implies, the Bimotore's distinction was that it had two supercharged straight eight engines, one mounted in the front, the other behind the driver, both engines somehow shoehorned into a special beefed-up chassis. It also had two hand cranks to turn over the engines, one under the grille and one in the rear. The two engines in the 6.3 litre Bimotore came right out of the Alfa Romeo P3: two 3.165 litre engines, which together developed 540 bhp and gave the Bimotore stunning top-end performance; the contemporary Mercedes-Benz developed 430 bhp and the Auto Union developed 375 bhp.

On May 5, 1935, the Grand Prix of Tunis, the first Formula Libre event of the season, was held in Tunis near what was formerly the classical Greek city of Carthage on the North African Mediterranean Coast. Alfa Romeo intended to run Nuvolari in the Bimotore at Tunis since it was one of the high speed circuits for which the Bimotore had been designed. But as it happened, the Bimotore manifested tire problems during testing, a harbinger of things to come, and Nuvolari ended up running an Alfa Romeo P3. Varzi won Tunis in an Auto Union; Nuvolari's P3 was out after a few laps.

On the next Sunday, May 12, 1935, the Tripoli Grand Prix was held on the exotic, palm tree-ringed 8.1 mile Mellaha circuit, also situated on the North African coast, in what is now Libya but which was then an Italian protectorate. Mellaha, with its long straights, was the fastest road circuit at that time, and thus a perfect opportunity for the Bimotore to show its worth. A large purse attracted 28 starting entries, including three Mercedes-Benz W25's, two Auto Union Type A's (one of them a closed-cockpit streamliner car for Hans Stuck) and a full Scuderia Ferrari team consisting of four Alfa Romeo P3's and the two new Alfa Romeo Bimotore cars.

The Grand Prix of Tripoli came at a time of personal turmoil for Rudolf Caracciola, who was still recovering both from a practice crash at Monaco in 1933 that injured his right leg (and from which he would have a visible limp for the rest of his life), and the loss of his wife Charly, who had been killed in an avalanche while on a skiing trip. The 1935 season would be Caracciola's opportunity to put these personal tragedies behind him.

In addition to the Bimotore's poor grid positions, Scuderia Ferrari was also worried about whether the Bimotore's (and their tires) would hold up for 40 laps on a hot and dusty track that was baking under the midday African sun. Tripoli's fine desert sand was also known to cause problems when it was windy as the sand blew across the track.

When the race got underway at 3 o'clock in the afternoon, Caracciola took the lead and Nuvolari managed to get into second place before having to pit after only 3 laps (roughly 25 miles) for fuel and tires. Luckily for Nuvolari, by lap 6, Caracciola's Mercedes-Benz W25 B was also in the pits because of a tire shredding. Achille Varzi in an Auto Union Type A and Luigi Fagioli in a Mercedes-Benz W25 B then took over at the front and were able to stay out longer before pitting, consigning Caracciola and Nuvolari to constantly playing catchup to Varzi who continued to maintain the lead. Meanwhile, Stuck's closed-cockpit, rear-engined Auto Union streamliner got too close for comfort when it caught fire, unbeknownst to Stuck, ultimately leading to Stuck's retirement at half distance.

After 30 laps, with only 10 laps left to go, Nuvolari's Bimotore was fourth and began to close the gap to Varzi's Auto Union, passing in the process the Mercedes-Benz W25 B's of Caracciola and Fagioli who were in second and third place, respectively. Caracciola, for his part, later explained that he let Nuvolari by, knowing that Nuvolari and Varzi would go at it hammer and tong. And he was right.

But Varzi's intense struggle with Nuvolari used up the tires on the Auto Union, and with just 5 laps to go Varzi's tires began to disintegrate and he had to limp back to the pits for new tires. By the time he was able to rejoin the race, Caracciola had taken the lead. Even so, Varzi's Auto Union, with fresh tires, relentlessly pursued Caracciola's Mercedes-Benz and caught him on the penultimate lap when, unfortunately for Varzi, the Auto Union blew another tire and Caracciola was able to cross the finish line first at an average speed of 123.03 mph, with Varzi second, Fagioli in the other Mercedes W25 B in third and the Bimotores of Nuvolari and Chiron finishing fourth and fifth respectively. The Grand Prix of Tripoli was to be the best team finish of the Bimotore's short but colorful career.

Two weeks later, the Grand Prix season continued back in Europe. On May 26, 1935, the Avusrennen Formula Libre race was held at the 5.1 mile Avus circuit in Berlin. Another large field of 22 entries was assembled, including streamliners for some of the drivers on the Mercedes-Benz, Auto Union and Alfa Romeo teams. Nuvolari and Chiron each raced a Bimotore.

Interestingly, the 1935 Avus race was Bernd Rosemeyer's first car race; the ex-motorcycle racer found himself turning the top speed of 326 km/h (195.6 mph) during practice on the Avus straights in his 375 bhp enclosed-canopy Auto Union streamliner. Indeed, the Avus track at this stage looked like two dragstrips joined together and was little more than two long two-lane autobahns with a slightly banked curve at the north end of the track and a hairpin at the south end. It was only in 1937 that the dramatic and infamous 43 degree Nord Kurve banking was added to the Avus circuit.

In the second 5-lap heat, it was Nuvolari's Bimotore teammate, Louis Chiron, who showed well, taking his Bimotore to fourth place. In the final race, Chiron took the Bimotore to its best result ever, second place to Fagioli in the Mercedes-Benz. Chiron's success was due to tire management: he had somehow learned how to be careful with the Bimotore's tires, while all around him the Auto Unions and Mercedes-Benz cars were bursting their tires.

Notwithstanding the efforts of Alfa Romeo and Auto Union, 1935 was a year that was destined to belong to Rudolph Caracciola and his Mercedes-Benz W25 B, and he was ultimately crowned European Champion for 1935, which signaled to the motor racing world that he had now recovered from his injuries and personal losses to return as a winner once again. Nuvolari in his Alfa Romeo was to enjoy a stunning triumph over the Silver Arrows later on in the Summer of 1935 at the German Grand Prix on July 28, 1935, where he emerged victorious over both the Auto Unions and Mercedes-Benz with guile and luck, but that was accomplished with an Alfa Romeo P3 with its engine tweaked to 3.8 litres, not with the Bimotore.

As an example, the Eifelrennen was held at the Nurburgring in mid-June 1935 and both Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union fielded four cars each but neither Nuvolari nor the Bimotore started the race. Why? Because Nuvolari and Scuderia Ferrari had decided to convert one of the Bimotore's to a Land Speed Record Car and join the speed record frenzy that was prevalent in the 1930's. Scuderia Ferrari built a lightened (weighing less than a ton) and streamlined version of the Bimotore that incorporated an aerodynamic fairing from the driver's headrest back over the engine cowling for the rear engine cover. On June 16, 1935, the Bimotore record car was successful in setting a new maximum speed record of 364 km/h (218.4 mph) and an average of more than 323 km/h (193.8 mph) over a kilometer distance - speeds reached on a stretch of the roadway from Florence to Livorno on the Italian coast.

By way of comparison to the Bimotore's achievement, today's land speed record "cars" are powered by turbojet engines from Vietnam-era Phantom fighter jets and have reached Mach 1 plus, over 763 mph, in places like the Black Rock, Nevada desert and the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, a long way from Tuscany. Interestingly, one of the current recordholders, the British Thrust SSC (Super Sonic Car), is also a Bimotore, sporting two jet engines.

It should be recognized that these land speed record attempts in the 1930's were not only trendy; they were also dangerous. On January 28, 1939, Bernd Rosemeyer's brilliant career was cut short when he was killed while participating in a speed record event in an Auto Union on the autobahn near Darmstadt, Germany, south of Frankfurt, while traveling at over 400 km/h (240 mph) when the car got caught up in a crosswind, may have become airborne and was swept into a bridge abutment. Rosemeyer was trying to break a record of 432.6 km/h (268.86 mph) set by Caracciola in the competing German marque; on his first run Rosemeyer managed to reach 429.92 km/h (267.14 mph).

Although in the end the Bimotore did not turn into the Silver Arrow World Beater that Scuderia Ferrari had hoped for in 1935, it continued to capture the imagination of race fans and car owners alike for years to come, as can be seen in the portraits of British privateer Arthur Dobson sitting in his Bimotore circa 1936 and in the pictures showing the Bimotore still being driven in anger and still looking sleek on May 1, 1937 at the inaugural race in England of the Campbell Circuit named after British land speed record holder Sir Malcolm Campbell. Indeed, the Bimotore purchased by Arthur Dobson from Scuderia Ferrari continued to be campaigned in one form or other until well after World War II, managing to finish second in the BRDC's 1948 Zandvoort Grand Prix in Holland and being associated with various distinguished owners along the way, including the Honorable Peter Aitken (who dubbed his modified Bimotore the Alfa-Aitken Special) and Major Tony Rolt.

The longevity of the Bimotore in its racing days continues in its retirement years. There are two extant Bimotores, an Italian Bimotore and an English Bimotore. The Italian Bimotore is a replica (though it has some original parts) and is prominently displayed at Alfa Romeo's museum in Arese, Italy, and, consistent with its joint parentage, the Italian Bimotore is sometimes loaned to Galleria Ferrari in Maranello, Italy, Ferrari's official museum.

The English Bimotore has a fascinating restoration history and is regarded as the sole surviving original Bimotore. According to Doug Nye in his History of the Grand Prix Car (1945-1965), the remains of the Alfa-Aitken were rescued by British collector Tom Wheatcroft and resurrected in as-original Bimotore form for his wonderful Donington Grand Prix Collection museum at Donington Park. Indeed, in a letter to the author from Kevin Wheatcroft, who, along with his father, Tom, runs the Donington Collection, it turns out that when Tom Wheatcroft found the car in Australia it still had many of its original components:

There are other differences between the two remaining cars. The Italian Bimotore and the English Bimotore are not identical as to the grille work and are also two slightly different shades of red, with the Italian car finished in the now long-gone, pre-Marlboro, traditional "blood-red" color and the English car painted a somewhat deeper red but both Alfa Romeos bearing the Ferrari insignia. The Italian Bimotore has silver-painted wire wheels; the wire wheels of the English Bimotore are the same red color as the body of the car.

But it does not really matter whether the crank handles on either of the two Bimotores is ever used again to turn the dual straight eight engines over: just standing there silently, even without the cacophony of 16 cylinders the Alfa Romeo Bimotore is a remarkable sight, wearing its short but distinguished role in the history of Grand Prix racing well and likely to continue to do so as long as the names of Alfa Romeo, Ferrari and, of course, Nuvolari, remain honored in the history of Grand Prix Motor Racing.

|

| Thomas O'Keefe | © 2000 Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. |

| Send comments to: okeefe@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |

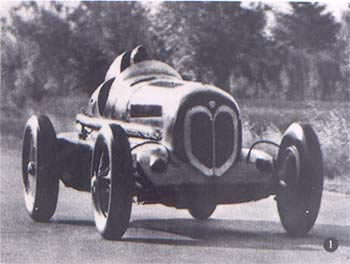

Although every inch an Alfa Romeo, the Bimotore was the brainchild of Enzo Ferrari and Luigi Bazzi, one of Ferrari's engineers at Scuderia Ferrari. In the early 1930's, Scuderia Ferrari had been delegated the responsibility for running the Alfa Romeo racing operation. Indeed, it is said that the 1935 Alfa Romeo Bimotore is the very first car to carry the now famous prancing horse insignia of Scuderia Ferrari on its flanks and above the Bimotore's valentine heart-shaped grille work. Simultaneously, the "Alfa Romeo" name is gracefully scrolled across the grille, the duality of the Bimotore extending even to its name!

Although every inch an Alfa Romeo, the Bimotore was the brainchild of Enzo Ferrari and Luigi Bazzi, one of Ferrari's engineers at Scuderia Ferrari. In the early 1930's, Scuderia Ferrari had been delegated the responsibility for running the Alfa Romeo racing operation. Indeed, it is said that the 1935 Alfa Romeo Bimotore is the very first car to carry the now famous prancing horse insignia of Scuderia Ferrari on its flanks and above the Bimotore's valentine heart-shaped grille work. Simultaneously, the "Alfa Romeo" name is gracefully scrolled across the grille, the duality of the Bimotore extending even to its name!

On April 10, 1935, approximately four months from the project's inception, Nuvolari began testing the Bimotore on the Brescia-Bergamo road, to determine if it was race-ready for the upcoming Grand Prix of Tunis in May 1935. But for all the straight line speed the two engines allowed the car to muster (upwards of 190 mph), it became clear that the Bimotore paid a severe weight penalty to accommodate the two engines and would be hard on tires; in addition, pictures of the car show an early form of pannier tanks running along both sides of the car to feed the thirsty beast, which also added weight to the Bimotore.

On April 10, 1935, approximately four months from the project's inception, Nuvolari began testing the Bimotore on the Brescia-Bergamo road, to determine if it was race-ready for the upcoming Grand Prix of Tunis in May 1935. But for all the straight line speed the two engines allowed the car to muster (upwards of 190 mph), it became clear that the Bimotore paid a severe weight penalty to accommodate the two engines and would be hard on tires; in addition, pictures of the car show an early form of pannier tanks running along both sides of the car to feed the thirsty beast, which also added weight to the Bimotore.

During practice for the Tripoli race, Stuck's Auto Union streamliner was fastest with 220.4 km/h (132.24 mph); Nuvolari's Bimotore was next fastest, ahead of Caracciola's Mercedes-Benz W25 B. But grid positions were determined by lot not by practice times at the Tripoli race and both Nuvolari's No. 42 Bimotore (starting halfway down the field) and Chiron's No. 56 Bimotore (which started in the last row) had unfavorable starting positions.

During practice for the Tripoli race, Stuck's Auto Union streamliner was fastest with 220.4 km/h (132.24 mph); Nuvolari's Bimotore was next fastest, ahead of Caracciola's Mercedes-Benz W25 B. But grid positions were determined by lot not by practice times at the Tripoli race and both Nuvolari's No. 42 Bimotore (starting halfway down the field) and Chiron's No. 56 Bimotore (which started in the last row) had unfavorable starting positions.

Italian rivals that they were, Nuvolari in the Bimotore and Varzi in the Auto Union put on quite a show, exchanging the lead as they fought wheel to wheel for first place, side-by-side motor racing at its best, a reprise of a similar battle they waged against one another in the 1933 Monaco Grand Prix. Finally, the Bimotore had to break off the duel to pit and Varzi continued in first place, with Caracciola in second place but one minute down from Varzi and both of them well ahead of the rest of the field.

Italian rivals that they were, Nuvolari in the Bimotore and Varzi in the Auto Union put on quite a show, exchanging the lead as they fought wheel to wheel for first place, side-by-side motor racing at its best, a reprise of a similar battle they waged against one another in the 1933 Monaco Grand Prix. Finally, the Bimotore had to break off the duel to pit and Varzi continued in first place, with Caracciola in second place but one minute down from Varzi and both of them well ahead of the rest of the field.

The race was run in three segments as two qualifying heats and a final race - the heats to be 5 laps each, the final race 10 laps - to minimize safety concerns due to tire degradation on the fast and demanding circuit and to maximize the interest of the fans. (The average lap time was almost 5 minutes so the fans had a longish wait to see the cars come around.) As predicted, tire wear proved to be the nemesis of several cars, including Nuvolari who had to make two pit stops in his Bimotore, the first one after only 2 laps (roughly 10 miles) of the first 5 lap heat. Nuvolari finished sixth in the first heat, more than five minutes behind the leader and not good enough to qualify for the final heat. Stuck's non-streamliner Auto Union B finished first, ahead of Fagioli's Mercedes-Benz W25 B.

The race was run in three segments as two qualifying heats and a final race - the heats to be 5 laps each, the final race 10 laps - to minimize safety concerns due to tire degradation on the fast and demanding circuit and to maximize the interest of the fans. (The average lap time was almost 5 minutes so the fans had a longish wait to see the cars come around.) As predicted, tire wear proved to be the nemesis of several cars, including Nuvolari who had to make two pit stops in his Bimotore, the first one after only 2 laps (roughly 10 miles) of the first 5 lap heat. Nuvolari finished sixth in the first heat, more than five minutes behind the leader and not good enough to qualify for the final heat. Stuck's non-streamliner Auto Union B finished first, ahead of Fagioli's Mercedes-Benz W25 B.

As for the Alfa Romeo Bimotore, it was sidelined for the balance of the 1935 Grand Prix season in favor of the more nimble Alfa Romeo variants better suited to the tighter, street circuits left on the calendar where the Bimotore's weight would be a disadvantage and its brute power not as useable.

As for the Alfa Romeo Bimotore, it was sidelined for the balance of the 1935 Grand Prix season in favor of the more nimble Alfa Romeo variants better suited to the tighter, street circuits left on the calendar where the Bimotore's weight would be a disadvantage and its brute power not as useable.

In October 1937, Rosemeyer on that same Darmstadt-Frankfurt autobahn had been the first to exceed 400 km/h (248.5 mph) on that road.

In October 1937, Rosemeyer on that same Darmstadt-Frankfurt autobahn had been the first to exceed 400 km/h (248.5 mph) on that road.

Finally, the Italian Bimotore has Alfa Romeo's insignia above the grille and the Ferrari symbol on the side of the car; the English Bimotore has Ferrari symbols above the grille and on its flanks with the Alfa Romeo insignia mounted on the grille itself. The schizophrenia of these cars continues to this day in the museums! While the English Bimotore has appeared at the Goodwood Festival of Speed and elsewhere for demonstration runs, the Italian Bimotore does not venture beyond the Museum; hopefully, Ferrari will someday sponsor an exhibit at an appropriate venue like Monza or Silverstone to bring both cars together so they can be viewed and raced side by side for the first time in 65 years.

Finally, the Italian Bimotore has Alfa Romeo's insignia above the grille and the Ferrari symbol on the side of the car; the English Bimotore has Ferrari symbols above the grille and on its flanks with the Alfa Romeo insignia mounted on the grille itself. The schizophrenia of these cars continues to this day in the museums! While the English Bimotore has appeared at the Goodwood Festival of Speed and elsewhere for demonstration runs, the Italian Bimotore does not venture beyond the Museum; hopefully, Ferrari will someday sponsor an exhibit at an appropriate venue like Monza or Silverstone to bring both cars together so they can be viewed and raced side by side for the first time in 65 years.