Atlas F1 Contributing Writer

Formula One arrives this weekend at the historic, and loved by most drivers, Spa-Francorchamps circuit, a track that, they say, separates the men from the boys. Journalist and historian Doug Nye looks back at the history of the Belgian circuit and reviews the most significant Grands Prix held there throughout the years

Martin Brundle is on record with this description of the place: "Absolutely one of my favourite circuits with some high-speed corners that really take your breath away, both metaphorically and physically. Spa is a real challenge and reminds you what being a Grand Prix driver is all about. It must rank as one of the most exhilarating places on earth at which to drive a Formula car." OK, praise indeed from a most perceptive and intelligent observer, yet one of the majority of Grand Prix drivers - i.e. one who never won a race.

Spa-Francorchamps' roads were first combined to host a gasoline sport in 1921, for motor-cycle racing. In 1925 the Belgian Grand Prix was run here for cars. The course became an annual home to long-distance races for sports and touring cars, using the full 9-mile (14.5-km) triangle. With the start, paddock and pits situated in the valley head near Francorchamps village, the course ran downhill past the later famous 'depots' into the left-hander over the little bridge crossing the Eau Rouge brook. In those days it continued to the left, climbing gently before a tight right-hand hairpin which brought the road climbing past a Customs House nestled in the brush and saplings on the right. The road then burst out onto the flank of the ridge at what today is the top of the famous Raidillon - the roller-coaster climb after Eau Rouge on the modern circuit. Zoom along the left-hand flank of the valley, climbing all the way to the ridge at Les Combes, where the modern circuit shears off to the right and plunges down into the valley floor.

This daunting place was victim of unpredictable weather. It was fast pre-war, and was made faster postwar as the RAC Belge indulged in a duel with the AC de Champagne and the Reims circuit in northern France for the claim to be the world's fastest Grand Prix road course. Spa-Francorchamps won as the Customs House hairpin had already been bypassed by the Raidillon, and postwar the Malmedy curve was opened out and the Stavelot hairpin was bypassed by a super-elevated short-cut. Ultimately this amazing venue would see the lap record raised to over 160mph, and all on everyday public roads with all the trackside hazards that entailed.

The Belgian GP postwar was a tremendous test of durability for driver and car alike. From 1962-65, the great Jim Clark's Lotus won four successive Belgian GPs - with luck squarely on the combination's side in several instances - and this record was matched by Ayrton Senna between 1988-91 in the McLaren-Hondas.

Unpredictable weather - isolated showers of rain on unexpected parts of the circuit - are always a problem in the Hautes Fagnes hills, never more so than in 1966, when the Grand Prix field started on a dry surface and ran into a violent rainstorm entering that eery, queasy downhill right-hander at Burnenville. Jack Brabham was well placed there: "I just found myself afloat and the car drifting wider and wider and wider without me being able to do a thing about it. I thought this is the big one. There was the dark trees and the bank coming up, and just at the track edge there was a low little kerb, and the tyres just kissed that and bumped me straight.and I lived to fight another day."

That episode served as a trigger to change the face of post-war Grand Prix history. Stewart was his generation's most promising new star and that incident at Spa shaped his commitment to improving - or in many ways 'introducing' - safety standards in or to Formula One.

Some critics misread Stewart's crusade. He wasn't a softy, fazed by danger. In 1967 he finished the Belgian Grand Prix second behind Dan Gurney's glorious V12 Eagle, driving his unwieldy BRM H16 one-handed for much of the race, holding it in gear.

After Pedro Rodriguez scored a brilliant victory for the BRM team in 1970, Spa-Francorchamps was dropped from the Grand Prix trail. The once great race fell victim to Belgian internecine politics between the Flemish and Walloons, Nivelles, near Brussels, and Zolder, near Hasselt, hosting what was styled as being 'The Belgian Grand Prix' cars up until 1983. It was then that Formula One returned to Spa to race on the modern shorter circuit, now 4.329-miles (6.968-km) to the lap. But this was not as seriously emasculated a course as many might have feared, for it has managed to retain much of the charisma generated by, and accorded to, its longer predecessor.

The new section plunged down into the primary valley floor to link the hill-top end of the long uphill main straight at Les Combes to the return leg of the old course before Blanchimont. The startline and modern-standard pits obliterated the old swampy, brush-filled infield at La Source hairpin preceding the still awe-inspiring plunge down the hill towards the climbing right-handed Raidillon slope beyond the Eau Rouge left-hander, demanding tremendous commitment and absolute precision from any drivers truly in contention for a competitive time. It survives today as one of the most challenging corners on any circuit anywhere in the world.

Savour this description of the modern course: "After hurtling through Eau Rouge, the cars begin the long climb towards Les Combes, which is a 190mph (306km/h) uphill sprint. This ends with an overtaking opportunity going into a medium-speed right/left-hander for those who have managed to exit on to the preceding straight a fraction faster than the competitor immediately ahead of them.

"There follows a plunging downhill sequence of bends, with no real chances for passing, which brings the cars back on to the old circuit at the 160mph (257km/h) Blanchimont right-hander. Then it is hard on the throttle once more for the return run back towards the pit area where the right 'bus stops chicane provides another

opportunity for the brave to have a stab at overtaking".

In 1993, the Lotus driver Alessandro Zanardi was involved in a huge accident at Eau Rouge from which he was extremely fortunate to escape unscathed. His Lotus had slammed into the right-hand retaining wall at about 150mph (24lkm/h), exciting concerns among the drivers about the proximity of the barriers to the edge of the tarmac at this point-

In 1994, the character of the circuit was changed considerably by the installation of a temporary chicane at the entrance to Eau Rouge. This was regarded as a necessary evil by most of the drivers, whose enthusiasm for this high-speed corner was understandably tempered by concerns for their own personal safety in a season that had already been marred by the fatal accidents to Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger at Imola three months earlier.

Happily, for 1995 the organizers substantially extended the run-off areas at Eau Rouge, which allowed the old corner configuration to be reinstated. The challenge to skill and car control was thus retained with a welcome safety margin added to cater for a loss of control or technical malfunction.

In 1993, Damon Hill scored a great win for Williams and followed that up with another win the following year, albeit inherited after Schumacher was disqualified for a technical infringement. Michael got his own back in 1995 with a terrific victory in treacherous wet/dry conditions, racing through from 16th place on the grid to beat Hill fair and square, then rammed home his status by winning again in 1996 at the wheel of the Ferrari F310.

In 1997 Schumacher returned to score a repeat victory for Ferrari, but this time he had no opposition whatsoever, dominating the race virtually from the start on a treacherously slippery track surface in his Ferrari. Second place fell to young Giancarlo Fisichella at the wheel of a Jordan-Peugeot, six years to the weekend after Jordan had given the unproven Michael Schumacher his maiden Fl outing right here.

But then spare a thought for the capabilities of the properly wired-up Formula One racing driver, even on such a frenetically fast and furious and lengthy course. A friend of mine working with Williams walked around the new backleg trans-valley link section of the course one year, and from the top of a hill looked way, way down upon his charges winding through that section, right, left, right, flick, flick, slide-correction-flick. He noticed one of his drivers raised a hand, as if to swat a fly, then back on the steering wheel, blaaaammm - out of sight. Next time round, there was the same movement. Strange, my friend shook his head and strolled back to the pits.

Later in the Williams motorhome, Jacques Laffite came bouncing in, "Hey!" he rapped, on seeing our mutual friend, "I waved to you out on ze back leg zere! Why you no wave back?". That's what it's going to take to win again at Spa this year - that indefinable spare capacity to rise to the challenge of this magnificent course, and to handle it with aplomb.

It's easy for a greybeard such as myself - one who has been utterly absorbed by racing since knee-high to an Alfa Romeo 159 Alfetta - to think instinctively of great Grand Prix courses in terms of that which they once were, rather than that which they now are. But the truth is that although every circuit still in use in the Formula One world today has been modified and modernized with safety absolutely the key, there are one or two - just one or two - which have still retained not only much of the old majesty, but which also provide today's drivers with much of the old - or near-equivalent - challenge. These are circuits which require, if you will excuse me use of a good old-fashioned Anglo-Saxonism...Balls!

And at the top of this particular tree is the Belgian Circuit National at Spa-Francorchamps. It is a shortened, cut-down version of the toweringly majestic, terrifyingly fast, old triangular loop of public roads which used to be used here in the Hautes Fagnes hills as the home of the Belgian Grand Prix, but it remains today a terrific circuit - and one which is much loved not only by competitors, but also by spectators.

And at the top of this particular tree is the Belgian Circuit National at Spa-Francorchamps. It is a shortened, cut-down version of the toweringly majestic, terrifyingly fast, old triangular loop of public roads which used to be used here in the Hautes Fagnes hills as the home of the Belgian Grand Prix, but it remains today a terrific circuit - and one which is much loved not only by competitors, but also by spectators.

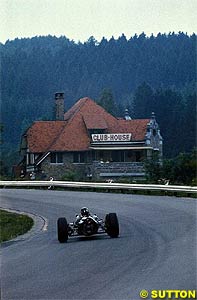

In the 'old days' it dived over the high ridge at Les Combes and slammed left, down into the next valley, flickering down through the mixed forests and farmland to the swooping, never-ending right-hander past the little inn at Burnenville. Still swerving right it passed the road junction to Malmedy - in World War 2 scene of the infamous 'Malmedy Massacre' - and then right again onto the start of the downhill, full throttle Masta Straight. Wiggle-woggle through between the houses at Masta Hamlet, straight again down through the fast curve at Hollowell - barely perceptible below 120mph - and then the course ran into the road-junction hairpin beneath the trees entering Stavelot village. Hard right here, and back through more swerves and curves, up the reverse side off the narrowing valley towards Francorchamps, through the dauntingly fast, narrow, tree-lined Blanchimont left-hander, then the almost equally tricky, rather shorter companion curve at 'Clubhouse' and up to La Source hairpin which today is the first turn of the modern shortened circuit.

In the 'old days' it dived over the high ridge at Les Combes and slammed left, down into the next valley, flickering down through the mixed forests and farmland to the swooping, never-ending right-hander past the little inn at Burnenville. Still swerving right it passed the road junction to Malmedy - in World War 2 scene of the infamous 'Malmedy Massacre' - and then right again onto the start of the downhill, full throttle Masta Straight. Wiggle-woggle through between the houses at Masta Hamlet, straight again down through the fast curve at Hollowell - barely perceptible below 120mph - and then the course ran into the road-junction hairpin beneath the trees entering Stavelot village. Hard right here, and back through more swerves and curves, up the reverse side off the narrowing valley towards Francorchamps, through the dauntingly fast, narrow, tree-lined Blanchimont left-hander, then the almost equally tricky, rather shorter companion curve at 'Clubhouse' and up to La Source hairpin which today is the first turn of the modern shortened circuit.

That's what it was like at Spa with the chips down and the spray rising. Further round that same lap Jackie Stewart was not so lucky in his BRM. He hit a river running across the road at Masta Hamlet, and spun into the stone abutment of a trackside barn. He was squashed, trapped, in his cockpit until freed by teammate Graham Hill and by Bob Bondurant - whose sister BRMs had spun off on the same water hazard. Bob's BRM ended upside down on the grass verge. He could smell petrol and could hear crackling. He thought "Oh No! Fire!", then the car was lifted off him, daylight - and raindrops - flooded in. The crackling had been the noise of helpers running through the trackside undergrowth to reach him.

That's what it was like at Spa with the chips down and the spray rising. Further round that same lap Jackie Stewart was not so lucky in his BRM. He hit a river running across the road at Masta Hamlet, and spun into the stone abutment of a trackside barn. He was squashed, trapped, in his cockpit until freed by teammate Graham Hill and by Bob Bondurant - whose sister BRMs had spun off on the same water hazard. Bob's BRM ended upside down on the grass verge. He could smell petrol and could hear crackling. He thought "Oh No! Fire!", then the car was lifted off him, daylight - and raindrops - flooded in. The crackling had been the noise of helpers running through the trackside undergrowth to reach him.

La Source hairpin as the first corner presented drivers with another tricky challenge, with a full grid of Grand Prix cars starting the race with a short sprint away from the start line before having to brake hard for the hairpin. A first corner collision became virtually inevitable, but by itself did something towards sorting out the hot-heads from the intelligentsia. Alain Prost's McLaren was clouted so hard here one year that it ran with its engine mounts bent - meaning that the whole car was bent like a banana amidships - for the entire race. Tadpole still excelled.

La Source hairpin as the first corner presented drivers with another tricky challenge, with a full grid of Grand Prix cars starting the race with a short sprint away from the start line before having to brake hard for the hairpin. A first corner collision became virtually inevitable, but by itself did something towards sorting out the hot-heads from the intelligentsia. Alain Prost's McLaren was clouted so hard here one year that it ran with its engine mounts bent - meaning that the whole car was bent like a banana amidships - for the entire race. Tadpole still excelled.

Senna's four consecutive victories served to set a new benchmark in terms of driving skill at Spa. Having previously won there for Lotus in 1985, the Brazilian was now firmly established as the most successful driver of all time on the Belgian circuit. Yet in 1992 victory fell to Michael Schumacher's Benetton, the young German thereby posting the first victory of a career that would see him establish himself as Fl's leading exponent in the post-Senna era.

Senna's four consecutive victories served to set a new benchmark in terms of driving skill at Spa. Having previously won there for Lotus in 1985, the Brazilian was now firmly established as the most successful driver of all time on the Belgian circuit. Yet in 1992 victory fell to Michael Schumacher's Benetton, the young German thereby posting the first victory of a career that would see him establish himself as Fl's leading exponent in the post-Senna era.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 8, Issue 35

Articles

A Question of Speed: CART vs. F1

Civil War of Motorsports: CART vs. IRL

Jo Ramirez: a Racing Man

Belgian GP Preview

The Belgian GP Preview

Local History: Belgian GP

Belgium Facts, Stats & Memoirs

Columns

The Belgian GP Quiz

Bookworm Critique

Elsewhere in Racing

The Grapevine

> Homepage |