Mike Doodson Turns 500

F1's Newbie Journalists

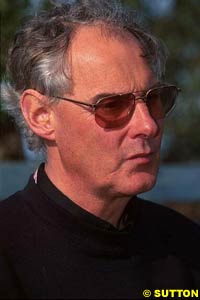

How many Grands Prix have you attended? How many of them have you spent in the vicinity of the drivers and teams? How many of them resulted in a race report, bearing your name, published around the world? There are only about half a dozen people who can respond to that with the amazing number of 500. And five hundred Grands Prix is exactly how many races journalist Mike Doodson has covered in more than three decades. Atlas F1's Biranit Goren (less than 30 GPs) and David Cameron (less than ten) met Doodson for a lesson on Formula One journalism, only to discover that what it really takes is being a true fan (and preferably from Britain). Exclusive for Atlas F1

Doodson's career spans across countries and publications: he began writing for Britain's Motoring News in the late 1960s; he worked with Autosport in the seventies; edited Motor Magazine until the early eighties; was part of the BBC F1 coverage team during the Murray Walker and James Hunt days; and in between was even the first uniformed team press officer, when he worked for the Lotus team during the 1972-1973 seasons. Nowadays, his articles can be found in newspapers and magazines in India as well as Colombia, but he is perhaps most recognised in Australia, where he writes for Auto Action, as well, of course, at his home land, England.

Fashionably for Formula One, where half the headlines are about the off-track controversies rather than the on-track racing, Doodson's first race out of 500 remains open for debate. He was sent to the 1969 French Grand Prix to cover the race for Motoring News in place of Dennis Jenkinson. But he never got to publish his report from that race, and the first Doodson-signed race report came in fact only at the beginning of the 1970 season.

"Jenks wasn't supposed to be at the 1969 French Grand Prix," Doodson explains, "but he submitted a report which had been compiled, one suspected, from the newspapers in England. He always said he was there, but we found his name in the results of a vintage motorcycle sprint, so I think it's safe to assume he wasn't at the 1969 French Grand Prix.

"But we decided that does count [as first of 500], because that race was actually a low point in Formula One: there were only 13 cars in the race, and so you could safely say that from the moment I appeared in Formula One the whole thing took off until it reached the present pitch! Mind you, I am not saying I'm responsible for Formula One's success - I suspect a small Englishman with grey hair and more money than I have could probably take credit for that."

Doodson is a funny guy. Sitting with him for over an hour in the media centre's coffee room at the A1-Ring could easily be the highlight of a young journalist's weekend. He has many anecdotes to offer, all in a typical old-school British sense of humour that is often poignant and dry. It's no surprise, then, to find out he was in fact educated to become an accountant - rather than a Formula One journalist.

"Yes, I did actually qualify as a chartered accountant," he says, "but I've been interested in racing since my father took me to Aintree, which was near our house, in the mid-1950s. I just fell in love with the sport straight away - I saw racing cars and thought, God, that's better than cricket or football!"

Q: You know, a lot of the drivers said the same thing - they caught the bug when they were children, going to the circuits with their father. So why did you turn to writing instead of driving?

"And then I took it out to Aintree, on a Tuesday evening. As I was braking for this corner on the club circuit, the entire Chevron works team went past me - among them Tim Schenken, driving a Formula 3 car, and Peter Gethin, driving an F2 car. They were both just cruising around, but the moment I hit the brakes, they passed me and just braked about 50 metres in front of me. I realised there and then I wasn't cut out to be a racing driver. And anyway, since the bank manager was about to foreclose on me I thought the best thing to do was sell the car."

Doodson had a spell as a marshall during his accountancy studying days, and became a full-time motorsport writer when his friend and Motoring News journalist Andrew Murray offered him his seat as the F2 correspondent. "That's the job he offered me," Doodson recalls, "and it didn't take much more than a nano-second to make that decision!"

Those Were the Days

In Austria, Toyota marked Doodson's 500th Grand Prix with a formal reception, and Doodson looked awkward with the shoe on the other foot. "I've never been interviewed before this weekend," he says, feeling slight discomfort at having to answer questions rather than ask them. "And besides, the whole idea of [celebrating] 500 Grands Prix raises a few insults, because people say '500 Grands Prix?!? You must have been covering races in the sixties!' And I'd say, 'yes, I was'. And they'll respond 'I had no idea you were that old!'"

Well, the 61-year old Briton is not that old, but in a sport that relies on memory and continuity his 32 years of experience and his natural ability to articulate stories with sheer fascination, make him a prime story-teller, far more interesting, sad to say, than any of the current drivers around.

"Well no other driver could match it, because no other driver's been around for 500 Grands Prix," he says. "But, you can find people here that are far more interesting than me. If you could get Patrick Head to sit down for that period of time, you'd get a lot more interesting stuff from him. And let me say that if you told Patrick Head, 'please can we talk for 10 minutes?' and you get him headed in the right direction, he'll end up sitting and talking to you for 45 minutes. Of course, if he thinks you're asking clever questions which are going to be used against him or his team, then he will give you the 10 minutes he promised and walk away. But if you show an interest in him and ask some intelligent questions, he can't stop himself."

Frankly, neither can Doodson - and those who listen to him are richer for that.

Q: OK, let's go back in time. How was the paddock back when you started covering Formula One? We always hear of how different the paddock is today

Doodson: "Well, if you look at the actual paddock of the French Grand Prix in 1969, the circuit was public roads and somebody said 'hey, that would be a good place to run a race, has anybody got a flag?' - and it was almost literally that. There was a small grandstand which probably had room for 300-400 spectators. The others just wandered in from the countryside, they just stood there on the side of the road, often a few feet away from the competing cars. It's just unimaginable by today's standards. It seemed entirely natural at the time.

"Then, the first time I went to the Canadian Grand Prix, in 1971, the press room consisted of a log cabin without any doors, a beaten earth floor, and the communications consisted of three pay-phones on the wall and a Telex machine that was permanently occupied. But of course, at the same time, I would say there was a good turnout if there were 50 journalists and photographers in any one Grand Prix - quite often it was fewer than that."

Q: So do you now, 30 years later, get nostalgic?

Doodson: "No, I never get nostalgic. You get nostalgic for things that you could have done better in the old days. You make mistakes and some of them you remember - but I have a very selective memory; I tend to remember all the good things and forget all the bad things. OK, yes, you get nostalgic for some things - I get nostalgic for this place, the old Osterreichring. I like this place, I like the idea of a circuit in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by cows. And it's just like it was when I came here for the first time in 1970. And we won't have it again, it's gone."

Q: Still, there's always this romanticising of 'the good old days' - and the inevitable suggestions that nowadays it's more commercialised, less of a sport

Doodson: "Well, you have to weigh one thing off against the other. In the old days, when I started, there were so few journalists that you could be friends with all the drivers. You certainly knew them. And there was a year where I think I knew the name of every single mechanic in the pitlane. But at the same time that you were friendly with the drivers, you were also always worried because there was a good chance they wouldn't be there after the race; they would be dead. These days you're not close to the drivers, because they're protected by all these ghastly PR teams, and they're all more likely to be there after the race than you are!"

Journalism 101

The fact that this interview is being published on an Internet website - 'the new media' - is a sign of the times for Doodson. He was in Formula One when fingers pounding on type-writers was the dominant sound in the press room; he's seen the first fax machine introduced in Japan (and preferred to travel to Tokyo to use a Telex machine, because he didn't trust that new invention called 'telefax'); and he's been there when laptops were first brought into the media centre, where nowadays hundreds of journalists from around the world occupy private phone lines, ADSL cables and cellphones aplenty. But the gist of the profession remains the same for him. Perhaps because 'profession' in itself is not what it's about.

"I've got a friend in Brazil who thinks nothing of covering a swimming match or an athletics meet - and then he shows up at the Grand Prix, and does an equally good job at them all. But I don't think he has the same affection for motor racing as I do."

Doodson is particularly loyal to the heritage of motor racing coverage of his homeland, which he sees as the true historians of the sport. "All the best books about the history of Mercedes or Ferrari or Maserati or Lotus or Brabham have been written by Brits," he exclaims. "One or two great books were written in foreign language, but most of the history of motor racing is safe in the hands of the Anglo Saxons."

Q: Yet Ron Dennis once famously told the press, 'we make the news, you only report it'...

Doodson: "Yes, and it was pointed out to Ron on that occasion that when McLaren is just a name in the official receivers' ledger, who will be writing the history of the team? We will. The British press. We get the last word; we always get the last word.

"Having said that, it's not a fixed rule because I can think of several journalists in each of the other languages who are just like me - they do it because they love it. And the other thing, of course, that's come in lately is the Internet. There's a new type of journalist working on the Internet; and they all seem to be living in Tel Aviv or Patagonia, and they're all bigger motor racing experts than I am!"

Q: You don't seem to be very impressed with the Internet...

Doodson: "Well, the Internet gets the information around very fast. But what I regret to see is that a lot of it is drawn directly from the teams' own press releases, which of course reflects only what the teams want you to know. The trouble is that the drivers spend so much time in briefings and being protected by their PR people, that you often don't get a chance to find out what's really happening.

"The end result: we had a very nice, old-fashioned pub-lunch with an old-fashioned mate-to-mate type conversation. He was happy - I paid the bill - I was happy, my editor was happy. I think even the Jaguar PR person was happy. Why couldn't it all be like that?"

Q: Another aspect of this, I suspect, is the fact that senior people in Formula One seem to have absolutely no qualms about lying time and again, and there's no accountability for it. You can ask Eddie Jordan if he's going to replace Sato and he'll deny it, and sure enough a couple of months later Sato leaves Jordan. Or ask Niki Lauda if Pedro de la Rosa remains in the team and he'll say yes, only to fire him a month later...

Doodson: "Well, you acquire experience over the years as to who are the people you can believe and who you can't. And I'm not going to identify anybody, but you have named one or two people whom we know are congenital liars. I'll give you another example of a congenital liar - somebody who lied throughout his relationship with me - and that was Ken Tyrrell.

"In 1970, a week before the Gold Cup, I heard that Ken Tyrrell would be running his own built car. So I rang him up and asked him. And he gave me a flat denial, and we published it on the front page of Motoring News, and the day after it was published, at the paddock in Oulton Park, was a brand new Tyrrell-Ford. So we knew going in that Ken Tyrrell, when it came to important things like that, would tell a lie. So you mark his card in your brain. And I got on extremely well with Ken Tyrrell and we had some wonderful interviews, and I believed what he told me. It was just on important things like that, when it was in his interests to keep something secret, he had no qualms at all about telling a lie.

"Ron Dennis once said to a colleague of mine, who accused Ron of lying, 'well of course I was going to lie, a billion dollars was involved.' This business of sassing out lies and whether you should trust people or not is entirely down to what previous experience you've had with these people, and I'm afraid you're only going to acquire that the hard way."

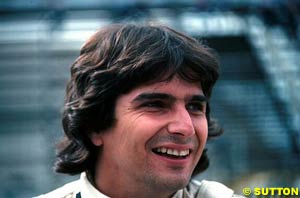

Mon Ami Piquet

Like many of his other veteran British colleagues, Doodson published a few Formula One related books, most notably was his very personal book on Nelson Piquet - a driver he readily admits remains his all-time favourite, "because he actually had a life outside motor racing," he explains.

Q: Is that because the Brits hated him because of the Nigel Mansell rivalry?

Doodson: "Well, there was an obsession with him, because they saw him as being the evil lad who upset our darling Nigel. And at that time most of the British press still hadn't seen through Nigel Mansell - who may have had his quality as a racing driver, but had his shortcomings as a human being.

"Nelson, though, was one of the cleverest drivers that I ever met. He used to win races by doing all the work before the race ever started. He got his car properly set up; he had the engineers on his side and that's where he put his human qualities to work. Most of the engineers who worked for him absolutely loved him."

Q: If Piquet was your favourite driver, what was your favourite team?

Doodson: "The same thing, really - for me the best team that there ever was, was the Brabham-BMW team of 1983, when BMW came back to win the World Championship from almighty Renault.

"At the beginning of the year I made a bet with Eric Bhat, the Renault PR man, that Nelson would win the Championship that year, while he said Prost would win it, and the wager was 50 dollars. We got towards the end the year and while at dinner, with Alain 14 points ahead in the Championship and clearly about to win it, Eric was taunting me - so I said 'alright then, if you're so sure let's increase the bet'. He said, 'ten times?' And I said 'OK, 500 dollars'.

"So I had 500 dollars riding on the final race of the season, and I won it. I was getting married about four days later and I didn't have 500 dollars, I can tell you..."

Q: How about your favourite driver among the current crop?

Doodson: "I like Montoya. I like his attitude. There are others I like too, but I don't know drivers as well as I used to. I met Cristiano da Matta properly for the first time at this race, and he seems like a nice kid. But I'll go for Montoya."

Q: Most memorable race?

Doodson: "Well, the Brazilian Grand Prix this year takes a bit of beating, doesn't it?

"But there was an Australian Grand Prix in 1991 which lasted for 14 laps, and that was pretty hectic too for the same reason, you know - rain. But if you set the climatic conditions aside I would have to say the South African Grand Prix of 1983 and me winning 500 dollars."

Q: How about your least favourite race, the race to forget?

Doodson laughs. "I've forgotten them!"

Q: Who isn't around anymore, that you miss?

"He felt passionately about motor racing. And you know, I invited him to one of my birthday parties and he showed up, with his wife! That was the sort of person that he was... if I invited Ross Brawn to my birthday party, I don't think he'd show up actually. So yes, I miss Harvey."

My Beating Heart

Being a Formula One journalist isn't always as fun as it seems - the frequent travel makes one's social life somewhat unstable, and many journalists and team workers have dropped out of the circus through the years. It makes Doodson's perseverance all the more astonishing, but he readily admits that F1 is, to a large extent, his own social circle.

"For motor racing journalists, a lot of the social life is at the races," he explains. "Nearly all of us travel with a group of friends and stay at the same places. It's very predictable."

Q: How do you maintain a family life like that, though?

Doodson: "My first wife actually worked with me in F1 for three years, so we had a good time traveling together, and thoroughly enjoyed our time together. But yes, of course it does place pressure, especially if you have kids. My first daughter was born one month before the 1987 season started, which seemed like a fair deal. But the second one was born 10 days before the Japanese GP of 1988 and I went off three days after she was born and phoned home as soon as I arrived in Tokyo to discover she'd got Jaundice. So I felt a bit helpless not being there to look after her...

"Still, it always surprises me how priorities change over the years. For example, Autosport's Mark Hughes took paternity leave when his children were born. So in other words, it's getting to be a job rather than a passion. Mark would probably deny that and say it's a passion for him too - and he does write passionately about the sport - but people have got different priorities now than they did when I was becoming a father."

Q: Nevertheless, with you doing this for so long, it does beg the question what is it that keeps you coming back? What keeps you interested in it?

Doodson: "What else am I going to do?? They changed all the accountancy laws in England twice since I qualified, and I wasn't a very good accountant anyway. Well, it's a good question - what keeps me coming back - and I've been asking myself the same thing recently.

"But I think the thing which I liked then and I still like now, is the companionship. Motor racing attracts exceptional people at all levels - whether it's the drivers at the top, or the engineers who look after them, or the managers who look after the teams, or, dare I say it, even the people in this press room. The people are exceptionally talented and it's great to mix with them."

Q: How much longer do you expect to do this, then?

Doodson: "You know, when I started this business I told my dad I'd probably be a GP reporter for a couple of years, and I've made a point and said, 'the moment the race starts and my heart's not beating fast, I've got to stop'."

Q: And that has yet to happen...

Doodson: "Actually, it did happen once! It happened at the 1979 French Grand Prix at Dijon, which is a circuit with very poor facilities.

"We went there on Sunday afternoon for the start of the race, and 10 minutes before the race started, the bleeding French police arrived and told us we were not allowed to stand there. So when the race started there was a huge fight between the journalists and the gendarmes about where we were going to watch the race! And once the race had started, the French - with typical decidedness - just melted into the background, and I realised the race had started and my heart didn't get going and I thought, 'oh dear, I'm probably going to have to be true to my principles and give up motor racing!'

"But that was actually the race in which Arnoux and Villeneuve were banging wheels for second place for the last three or four laps - and that made up for missing the start, because I can tell you my heart was going pretty strongly by the time!"

Q: Does your heart still go like that, pound at every start?

Doodson: "Yes, yes, still. There's nothing more exciting on earth than 20 cars with 800 horsepower and the 20 best drivers in the world all ready to do battle, down to the first corner. I'll never get tired of that."

With Mike Doodson taking such pride and patriotism in the British Press, it was the perfect opportunity to find out, once and for all, why the British press hates World Champion Michael Schumacher so much.

"Why do you think it's the British press?" Doodson snaps, when asked.

Q: Well, I don't think I'm alone in getting that impression. In fact, I think Schumacher himself once stated as such

Doodson sighs. "All right then," he says in a stern voice, "I'll answer your question.

"I said that the history of motor racing is safe in the hands of the Anglo Saxons, and I think I'm right there. I think there is more history of motor racing written in English than in any other language. And let's face it, because we're not professional journalists, we're fans, the Brits tend to be the most senior people in Formula One. Therefore, we've seen more great drivers than most of the other nationalities. Therefore, when we evaluate the drivers we are perhaps in a better position to isolate or identify their flaws. And I think it's safe to say the British press are agreed that Schumacher is a seriously flawed driver.

"He seems to make a lot of mistakes, too. How many times did he spin here [at the A1-Ring] on Friday? And he was nearly off the road yesterday, in Saturday's qualifying. That raises question marks about him. And there are other question marks about him and his team, which I am not going to go into now, but as time passes, things emerge. Not everything emerged about what happened in 1994, but we all have a pretty good idea.

"But if there's one thing that's wrong with Michael Schumacher is that he has no sense of motor racing history. Senna, for example, had a fantastic sense of history. And when Juan Manuel Fangio showed up at the Brazilian Grand Prix in 1991, that gave Senna even more incentive to win the race. He wanted to win the race in front of the man he admired more than anybody else, and he did - it was a very emotional win! Somehow I don't see that happening with Schumacher."

Last year's Monaco Grand Prix was the first time journalist Mike Doodson did not attend the famous race at the principality since 1967, and the first Grand Prix he didn't attend in two decades. Falling ill, he watched the race at home in England, on the Sky digital coverage, and once the race was over he drove to his office and submitted a race report, as he always does. "But I finished it a couple of hours before I'd have finished it if I was at the Grand Prix, and I got an early night's sleep!" he exclaims, which perhaps suggests that F1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone had a point when he told the journalists, some 8 years ago, that they'd be better off staying at home and watching the Grands Prix on his television feed. "He said: 'You'd get more information from me than you do from the bloody teams'," Doodson recalls, laughing.

But Doodson himself is living proof that history is not written by those who stay at home and watch the TV. With 500 races under his belt as a Formula One journalist, Doodson is among half a dozen other journalists who have been covering the sport for over three decades. Along with a few dozen others who have already notched up several hundred Grands Prix Doodson is, by and large, responsible for how the fans perceive Formula One, the races, the teams, the drivers. He is the historian and the messenger. And, above all, he is - still, one should add - among the sport's greatest fans.

But Doodson himself is living proof that history is not written by those who stay at home and watch the TV. With 500 races under his belt as a Formula One journalist, Doodson is among half a dozen other journalists who have been covering the sport for over three decades. Along with a few dozen others who have already notched up several hundred Grands Prix Doodson is, by and large, responsible for how the fans perceive Formula One, the races, the teams, the drivers. He is the historian and the messenger. And, above all, he is - still, one should add - among the sport's greatest fans.

Doodson: "Well I did turn myself to driving, actually. I bought myself a little U2 car - like a Lotus 7, front-engined, with a lot of standard production parts on it. I built that with a friend in my spare time - it was a second-hand car, and I knew the bloke who'd driven it, in fact I've seen him drive it several times and fallen in love with the car. But I really shouldn't have bought it because I couldn't afford it and I bankrupted myself virtually building that car.

Doodson: "Well I did turn myself to driving, actually. I bought myself a little U2 car - like a Lotus 7, front-engined, with a lot of standard production parts on it. I built that with a friend in my spare time - it was a second-hand car, and I knew the bloke who'd driven it, in fact I've seen him drive it several times and fallen in love with the car. But I really shouldn't have bought it because I couldn't afford it and I bankrupted myself virtually building that car.

"The paddock was on a slope, and it was volcanic earth which was so sharp that when they brought the cars up from the paddock to the pits, they had to fit them with rain tyres or otherwise they'd have punctured all their tyres. The pits consisted of a few concrete sheds - you could get three people in from each team if it rained, and many of the pits didn't even have roofs, because they probably fallen in. It really was ramshackle, that's the only way to describe it.

"The paddock was on a slope, and it was volcanic earth which was so sharp that when they brought the cars up from the paddock to the pits, they had to fit them with rain tyres or otherwise they'd have punctured all their tyres. The pits consisted of a few concrete sheds - you could get three people in from each team if it rained, and many of the pits didn't even have roofs, because they probably fallen in. It really was ramshackle, that's the only way to describe it.

"I think if you look at the different language groups you'll find that the British journalists are different from most of the others, insofar as the majority of the British journalists - I set aside the 'fleet-street' guys - are like me: they are enthusiasts," he explains. "They are people who went to motor races as kids, fell in love with it and never wanted to let go of it. Whereas a lot of the foreign people, the continentals, tend to be people who trained as journalists - and very few Brits have trained as journalists, I can't think of any actually - and who therefore can turn their hand to any kind of sports reporting.

"I think if you look at the different language groups you'll find that the British journalists are different from most of the others, insofar as the majority of the British journalists - I set aside the 'fleet-street' guys - are like me: they are enthusiasts," he explains. "They are people who went to motor races as kids, fell in love with it and never wanted to let go of it. Whereas a lot of the foreign people, the continentals, tend to be people who trained as journalists - and very few Brits have trained as journalists, I can't think of any actually - and who therefore can turn their hand to any kind of sports reporting.

"I had an experience this year when my magazine wanted me to do a story with Mark Webber. I rang up his publicist and made an appointment - we made an appointment in a pub, on a Saturday at lunchtime. And the day before I went, I got an e-mail from the Jaguar press officer saying 'would you please be so kind as to give me a list of the questions you're going to be asking Mark Webber.' So I wrote back to her saying: 'one, in the 32 years I've been doing this job I've never yet submitted a list of questions to anybody and I hope you forgive me if I don't start now; and secondly, even if I agreed to supply the list I wouldn't be able to because we're going to have lunch in a pub and I shall ask the questions as they come up!' And that was the last I heard from her.

"I had an experience this year when my magazine wanted me to do a story with Mark Webber. I rang up his publicist and made an appointment - we made an appointment in a pub, on a Saturday at lunchtime. And the day before I went, I got an e-mail from the Jaguar press officer saying 'would you please be so kind as to give me a list of the questions you're going to be asking Mark Webber.' So I wrote back to her saying: 'one, in the 32 years I've been doing this job I've never yet submitted a list of questions to anybody and I hope you forgive me if I don't start now; and secondly, even if I agreed to supply the list I wouldn't be able to because we're going to have lunch in a pub and I shall ask the questions as they come up!' And that was the last I heard from her.

"You can study Senna or Schumacher, and their obsession makes them rather uninteresting as human beings," he says. "And I like human beings. And for that reason I like Nelson. There was much more to him than he let on - he didn't hide it, just that a lot of people didn't bother to find out what he was like. No other British journalist ever bothered to sit down with him and get to know him."

"You can study Senna or Schumacher, and their obsession makes them rather uninteresting as human beings," he says. "And I like human beings. And for that reason I like Nelson. There was much more to him than he let on - he didn't hide it, just that a lot of people didn't bother to find out what he was like. No other British journalist ever bothered to sit down with him and get to know him."

Doodson ponders the question for a moment, then requests to think about the question a bit longer. A few moments later, though, he says: "I miss [F1 designer] Harvey Postlethwaite (who died in 1999). He was not only a very good engineer, but he was also a top rate human being. Terrific sense of humour, terrific sense of tolerance. He loved cars and he was like me: he loved all the old-fashioned things that the Flavio Briatores and one or two of the others in this world couldn't care a stuff about.

Doodson ponders the question for a moment, then requests to think about the question a bit longer. A few moments later, though, he says: "I miss [F1 designer] Harvey Postlethwaite (who died in 1999). He was not only a very good engineer, but he was also a top rate human being. Terrific sense of humour, terrific sense of tolerance. He loved cars and he was like me: he loved all the old-fashioned things that the Flavio Briatores and one or two of the others in this world couldn't care a stuff about.

"There was a room where we could work, but there were no TV sets and there were no windows, you couldn't see anything in the press room. There was also no place for us to stand around the track, except for an open space on the outside of the first corner, and you could stand there, and you could see the cars come up the hill along the straight and go into the pits, so you could keep a lap-chart pretty accurately. And all through Friday and Saturday and Sunday morning, nearly all of the journalists stood out there, at the outside of this corner.

"There was a room where we could work, but there were no TV sets and there were no windows, you couldn't see anything in the press room. There was also no place for us to stand around the track, except for an open space on the outside of the first corner, and you could stand there, and you could see the cars come up the hill along the straight and go into the pits, so you could keep a lap-chart pretty accurately. And all through Friday and Saturday and Sunday morning, nearly all of the journalists stood out there, at the outside of this corner.

Sidebar: The British Press Vs. Michael Schumacher

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 9, Issue 23

Atlas F1 Exclusive

Keeping Track: Mike Doodson Turns 500

Ann Bradshaw: View from the Paddock

Monaco GP Review

2003 Monaco GP Review

Crossing Over the Jordan

The Forgotten Men

Stats Center

Qualifying Differentials

SuperStats

Charts Center

Columns

Season Strokes

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |